Alan Carr has never cared much for cats. But in a strange quirk of fate, he’s found himself the proud owner of 926 CryptoKitties. For the past two years, he’s obsessed over the digital collectibles, culminating in him landing a job as a product designer at Axiom Zen, the company behind CryptoKitties in March 2018.

“This is my Ikigai,” Carr told Decrypt, referencing a Japanese concept which roughly means one’s passion in life. “This is the intersection of something I’m interested in, something I’m good at, something that is helpful to the world… and something I can get paid for. As soon as CryptoKitties came out, I knew that I wanted to be in the space and I wanted to be building.”

For Carr, CryptoKitties was a compelling use case for blockchain technology, and its ability to tokenize assets.

Toward the end of 2017, he didn’t have the disposable income to invest in a substantial amount of bitcoin. The price per coin was around $18,000 at that time, plus bitcoin didn’t feel like something a person could really interact with. Sure you could day trade and buy and sell alts, but that wasn’t what Carr was interested in; it felt more like work.

“CryptoKitties was very tangible despite being digital. The smart contracts and tools were all open and right there in front of you,” he said.

He bought his first CryptoKitty in December 2017 for $40, which “felt like a lot at the time—I’m spending $40 on a picture of a cat!?” But after that purchase, he was hooked.

“I owned a digital asset and I could see [that ownership] on the blockchain. I had full control and it felt powerful,” he said.

So he bought another, and bred them, and then sold the offspring.

Did you know?

The most expensive CryptoKitty, named Genesis was valued at $114,481.59 at one point. That's more than the most expensive 'real' cat on record, which only cost $41,435.

“It was just this magical experience that I had created this digital asset out of kinda nothing. I did it a few more times and then sold one for the first time. I mean I was making money off this asset I had created. It wasn’t something I had bought and resold,” Carr continued. “That was also super powerful to me and I really fell deep into that rabbit hole and started transferring more and more and more of the money I had into Ethereum.”

The time B.C. (before CryptoKitties)

It was a revelation. For years, Carr, 37, had been bouncing between industries.

Bubbly and energetic, Carr is the kind of person who enjoys thoroughly learning about a subject, so that even the most mundane task can be exciting. In early 2006, Carr scored a job working as the gamemaster on World of Warcraft at Blizzard Entertainment. After the birth of a child, his wife wanted to be a stay at home mother, so the family moved to Las Vegas, where he planned to create smartphone games.

But that, and his published novel, weren’t paying the bills.

Kitties were the first time many of us were exposed to an actual, usable, digital asset which we owned

When he stumbled into CryptoKitties however, Carr believed he’d fund something that was not only remunerative, it had the potential to change the world.

“Tokenization to me is just a way of quantifying or encapsulating something which may normally be an abstract concept, like ‘ownership’ or ‘my wizard’s power,’” Carr said. “It’s a metaphor that lets you think clearly about a series of rules that govern how you interact with a given set of data.”

Oh, you fancy

Once he got started with CryptoKitties, he couldn’t stop. He bought another CryptoKitty and then another, and started hanging out on the forums and subreddits dedicated to the game. There was a whole subculture surrounding the game, especially as it related to mapping the gene code of “Fancies,”—Cryptokitties that are identified by their custom artwork, such as CryptoKitties that weren’t cats at all, but were ducks, and their ability to be bred only a limited number of times. That them (and their offspring) particularly rare—and potentially valuable.

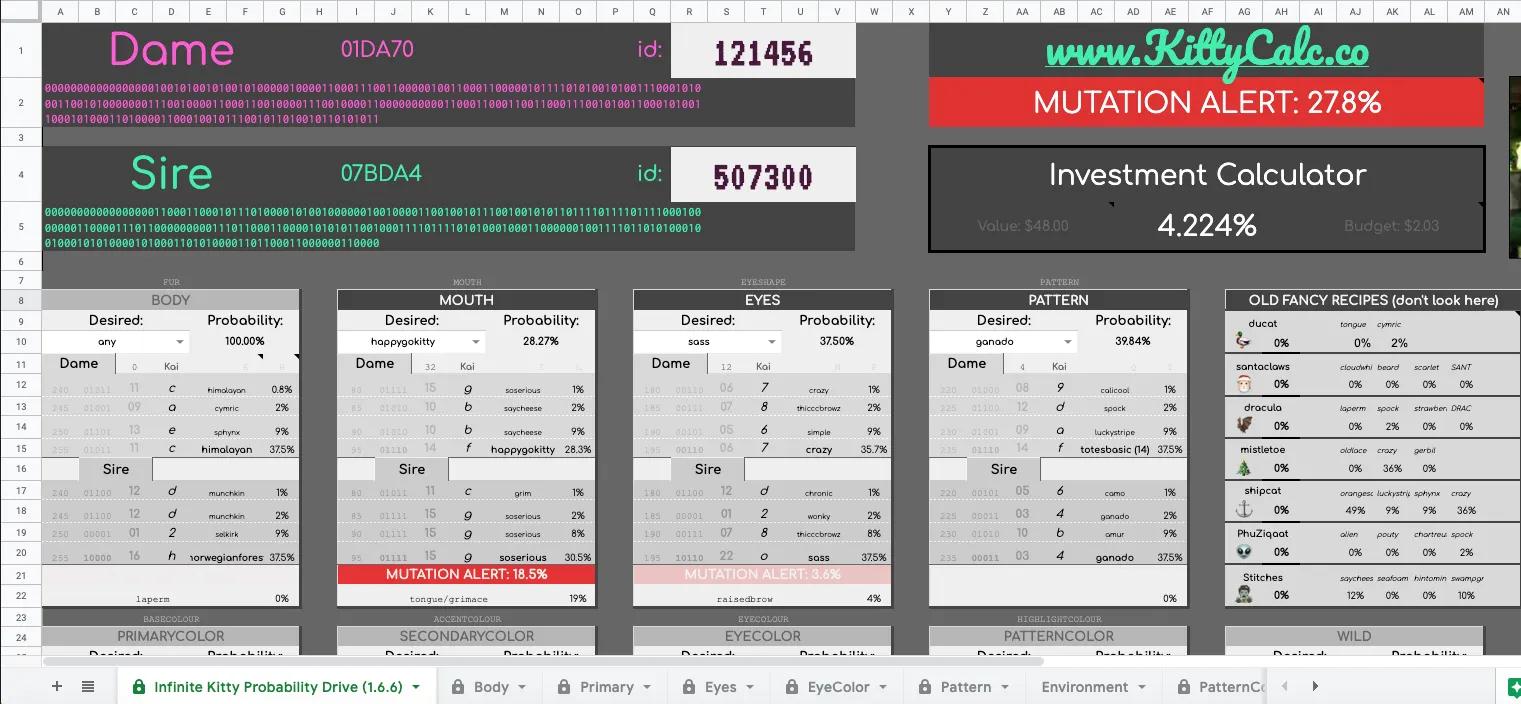

As users of the game began investigating the source code in an effort to figure out how to “make” a Fancy, Carr began putting this data into “a very complicated spreadsheet.”

Getting the kitty gene data directly from the blockchain and running probabilistic calculations, Carr began putting percentages on all the cats and their qualities. For instance, a blue cat might have a 20% chance of creating a blue cat if it “bred” with a white cat, or a striped cat with wings might have a 30% chance of creating a rare fancy if bred with a duckcat.

“That was consuming all my time,” Carr said.

And he wanted to share the spreadsheet with others, but as a spreadsheet, many people were intimidated by its complexity. So Carr approached another CryptoKitties user, Jordan Castro, to help him build a user-friendly rating site for CryptoKitties breeding.

That was the start of KittyCalc, which ended up being a wildly popular calculator for determining what attributes two cats might spawn. Carr and Castro were able to monetize the site, by allowing specialty breeders and people with valuable, breedable cats to advertise on the front page.

“This was all done without talking to the CryptoKitties folks about it,” Carr said. “It was all because of blockchain that this was possible.”

Joining the litter

Carr did eventually talk to CryptoKitties.

One day in February 2018, he reached out to Roham Gharegozlou, CEO of Dapper Labs Inc. Gharegozlou had tweeted, wondering whether it was possible to make a prediction tool for the game, and Carr knew that he and Castro could, in fact, build it. Intrigued, Gharegozlou flew Carr and Castro to CryptoKitties’ HQ in Vancouver.

A month later, both men were working at CryptoKitties.

“One of the most impressive things about meeting Alan was the passion he has for CryptoKitties and its community,” Gharegozlou told Decrypt. “He obviously cares deeply about CryptoKitties and what it means for the future, but he backed up his optimism with a variety of meaningful suggestions for improving the product. Moreover, his feedback was supported with solid reasoning, input from the community and actionable ideas for seeing them to fruition.”

Tokenization to me is just a way of quantifying or encapsulating something which may normally be an abstract concept, like ‘ownership’ or ‘my wizard’s power.

These days, Carr is working on the NBA (National Basketball Association) platform for crypto-collectibles, featuring specific player’s moves, such as dunks, blocks, and shots. For him, the NBA partnership will make CryptoKitties, and the broader crypto-collectibles concept, a mass-market experience.

“A lot of people have trouble telling their family and friends about buying thousands of dollars worth of Kitties,” Carr said. “The NBA project will have a lot of the same hyper engagement and excitement but people won’t be low-key ashamed that they own one.”

Although Carr doesn’t think CryptoKitties is anything to be embarrassed about really.

“Kitties were the first time many of us were exposed to an actual, usable, digital asset which we owned,” he said. “Not only did it spawn a host of copycats, but it also opened the doors in the minds of many people like me… for what it would be like to have access to a wide range of tokenized digital assets.”

Those possibilities include a growth in decentralized games where characters can be ported from one game to others, or be maintained even if the company that created them goes out of business.

In fact, when the CryptoKitties website was down, Carr figured out how to use tools such as EtherScan and MyEtherWallet to breed his cats directly.

And that’s what really struck a chord with Carr. Years ago, Carr invested a lot of time and money into a game called City of Heroes, which was shut down, leaving the characters that the game’s dedicated fan base had created inaccessible. “My assets were gone; the money and time I invested into them was gone, and I can’t share that game with my children ever,” Carr said. “So I love the doors that these crypto experiences can open.”

Carr continued: “It’s a first-world problem, sure, but it’s still a problem.”